DominionSections

Browse Articles

- IndependentMedia.ca

- MostlyWater.org

- Seven Oaks

- BASICS Newsletter

- Siafu

- Briarpatch Magazine

- The Leveller

- Groundwire

- Redwire Magazine

- Canadian Dimension

- CKDU News Collective

- Common Ground

- Shunpiking Magazine

- The Real News

- Our Times

- À babord !

- Blackfly Magazine

- Guerilla News Network

- The Other Side

- The Sunday Independent

- Vive le Canada

- Elements

- ACTivist Magazine

- The Tyee

- TML Daily

- New Socialist

- Relay (Socialist Project)

- Socialist Worker

- Socialist Action

- Rabble.ca

- Straight Goods

- Alternatives Journal

- This Magazine

- Dialogue Magazine

- Orato

- Rebel Youth

- NB Media Co-op

Radio

Drawing a Response

August 25, 2004

Drawing a Response

With simpler media, complex work appears

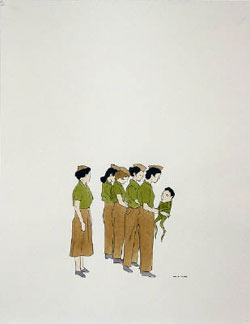

Marcel Dzama, "Untitled"

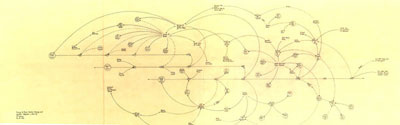

Mark Manders, "Self Portrait as a Provisonal Floor Plan"

Shary Boyle, "Untitled"

Suddenly, drawing is in. This new artistic trend has been publicized and sanctified by the great determiner of what's hot and who's who, the Whitney Biennial; by galleries across Canada and the US; and by the art sections in independent booksellers. Being excited yet suspicious of fashionable art is only natural. Has drawing become popular because the Art World has announced a new trend in taste, or is there another reason that so many artists are returning to this medium?

The answer is in the forms that many of these new drawings are taking. No longer do they fulfill former roles of sketches, preparatory studies, or documents of action. These drawings are finished pieces of work and show an affinity to popular illustration. Graphic design, architectural plans, scientific illustration, comics, and detailed diagrams are frequently appropriated. A natural assumption to make when artists are returning to a more direct medium such as drawing is that artists are reacting against the rise in the arts of "cold" scientific-electronic mediums. Yet the drawings are more of a hybrid between popular culture, computerized images, and high art than a reaction against computer-driven art. Julie Mehretu's main source material comes from computers and the Internet, for example. The appropriation of popular visual illustration is an appropriate of a language. Laura Hoptman, former assistant curator of The Museum of Modern Art's Department of Drawings, likens drawing to language, as "certain visual conventions are codified by mutual agreement and exist to ease communication." The drawings have something to say, and they use familiar, though distorted, media to communicate.

Mark Lombardi is best known for his attempts to communicate the complexity of corruption. His drawings are diagrams using circles and arrows, which he calls a narrative structure, "because each consists of a network of lines and notations which are meant to convey a story, typically about a recent event...like the collapse of a large international bank." Lombardi's work charts political and financial intrigue in a readable, recognizable map, but its strength comes from the dizzying sense of the flow of power and capital.

Like Lombardi, Julie Mehretu makes a type of map; she uses her computer and architectural samples to make massive drawings of beautifully chaotic cityscapes. Yet, because her source material is not organized geographically or chronologically, her maps are of places anywhere at any time (or no where at no time, depending on whether your glass is half-full or half-empty). Both Mehretu's and Lombardi's drawings use organized chaos to create a sense of vertigo.

Amy Cutler and Shary Boyle turn to alternate heroines in their cartoon-influenced narratives. The characters in these drawings are usually hybrid human-animals, or human-objects, and the accompanying narratives are frequently humorous and subtly ominous. Marcel Dzama's creepy anti-heroes enjoy a semblance to horror movie and pulp romance characters, together at last. All three artists, especially Cutler and Dzama, are enjoying a popularity usually reserved for Star Trek; their narratives depict the grotesquely heroic and the lightheartedly uncanny.

There are also artists such as Matthew Ritchie who use both diagrams and character-narratives. Ritchie's enormous pieces have rules and game strategies that are meant to map an imaginary (though somewhat similar) world from its genesis, and have characters and themes that recur throughout his art. His work encompasses more than a viewer can take in, and his "maps," unlike Lombardi's, are not meant to be easily read, but like Lombardi's give an overarching sense of interdependency and saga.

All of these artists are using the established language of popular illustration to create a rational plan of an alternative world. They are drawing alternative explanations and new mythologies for us. But alternative to what? New to what? Each work sidesteps established myths of normalcy. Lombardi's work runs under the facade prepared by market leaders to retrieve an original lie. Mark Manders, Amy Cutlers, and Shary Boyle tell a tale parallel to reality, but recovered, like Narnia. With our continent's current brand of political turmoil, the drawing trend is well timed.

Julie Mehretu, "Retopistics"

Mark Lombardi, "George W. Bush, Harken Energy, and Jackson Stevens, c. 1979-90"

Related articles:

By the same author:

Archived Site

The Dominion is a monthly paper published by an incipient network of independent journalists in Canada. It aims to provide accurate, critical coverage that is accountable to its readers and the subjects it tackles. Taking its name from Canada's official status as both a colony and a colonial force, the Dominion examines politics, culture and daily life with a view to understanding the exercise of power.